|

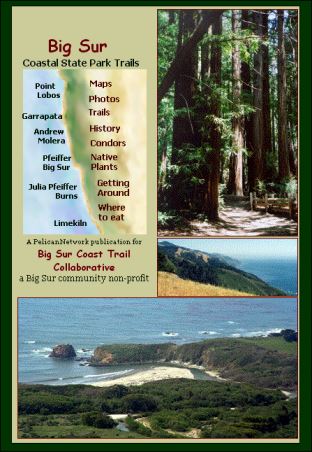

Table of

Contents

|

|

3

Point Lobos

5

Garrapata

8

Andrew Molera

13

Pfeiffer Big Sur

16

Julia

Pfeiffer Burns

29

Limekiln

Maps

Big Sur

History

People

of Big Sur

Getting

Around Big Sur

Wildlife

of Big Sur

Native

Plants

Redwoods

Rich

Marine Environment

Backcountry

Songbird

Banding

Where to

eat

|

|

|

By

Jack Ellwanger and Margie Whitnah

PelicanNetwork

PO Box 222224

Carmel, CA 93922

Big Sur Coast Trail

Collaborative

Community-based

initiative to complete the California Coastal

Trail

PelicanNetwork.net

/bscoasttrail.htm

To order

copies of Big Sur Coast Trail Guide

call 831 667 2025

|

Wondrous scenery and amazing biodiversity in the Santa

Lucia Mountains along the coast make Big Sur a treasure

of nature.

Good

trails and spectacular country.

Not as high, but

steeper than the Sierra, and more diverse. Big Sur and

the Ventana Wilderness offer challenges. The broad

biodiversity, newborn geology, and the closeness of the

ocean all combine to engage your senses in unexpected

ways.

Page Two

|

|

Point Lobos

State Reserve

2 miles south of

Carmel’s Rio Road

$8 Park entrance fee per car

|

Point

Lobos

is the product of

complex geology. Blocks of earth from three miles

deep, parts of the Sierra Nevada mountains and some

Pacific islands off southern Mexico collided here.

The sparkling granite cliffs that came from deep

beneath the sea, emerged as molten lava and cooled

very slowly. Here the unique geology cleanses the

sea. A great progression of change is evident in

the meadows and coves throughout Point

Lobos.

This is another world, and

it seems that each step brings a hiker to yet

another visual wonder.

Mercifully spared the

developer’s bulldozer early in the last century,

Point Lobos has been preserved as a California

State Reserve.

Its rare beauty and unique

biology have made it a symbol of California Parks

and the Monterey Bay National Marine

Sanctuary.

It may seem peaceful now,

but Point Lobos has a raucous history.

|

|

China

Cove China

Cove

Photo by Jack

Ellwanger

|

In the more than 750 land

acres of Point Lobos State Reserve, there are 14

trails covering 6 miles.

The hikes along the coast

are stunningly beautiful…along ledges through

ancient cypress overlooking storybook coves…unto

headlands lavished in rare flora and staged with

great birds. The hikes inland into meadows and

forests are more subtle and yet filled with intense

nature.

An excellent trail map and

description is available at the Ranger Station at

the entrance to the Reserve. There’s a fee for

vehicles – but no fee to bicycle or to walk in. If

110 visitor vehicles are already in the reserve,

more will not be let in until those earlier cars

leave. That situation can often happen early when

the weather is nice.

Point Lobos State Reserve

opens at 9:00 a.m. Visitors must leave the Reserve

by the closing time listed

Winter closing time –

Pacific Standard Time: begins Sunday, October 29,

2006

No admittance after 4:30

P.M.

Summer closing time –

Daylight Savings Time: begins Sunday, March 11,

2007

No admittance after 6:30

P.M., all visitors must exit by 7 P.M. at the

Ranger Station.

Be well-prepared for

taking photos, as there are far more photographic

opportunities than you can imagine.

|

|

|

|

|

Page Three

|

|

North Shore Trail

Along the Carmel Bay, starting at Whaler’s

Cove, this trail quickly ascends to great views of

isolated beaches filled with steller seals (Lobos

marinos – the name given to the sea lions by the

Spanish). On this very gratifying 1.5-mile hike,

you’ll see tantalizing sights of offshore rock

islands, ancient trees, nesting sea birds.

Note: Visit

the Whaling Museum at Whaler’s Cove – Along with a

great collection of cultural and natural history,

it includes a lot of movie memorabilia from films

made here.

Sea

Lion Point

Trail

A half-mile trail to incredible ocean views and

a good look at the reserve’s plant communities and

geology. Wheelchair accessible.

|

|

|

Bird

Island

Trail

A 3.5-mile loop trail to sea otters and birds.

It includes a loop trail down to Gibson Beach and

back.

South Shore

Trail crosses a rocky area to a bluff

where you can see Bird Island. It passes two

idyllic, sandy beaches accessed by wooden

stairs.

Bring binoculars. Watching the life on Bird

Island can be enthralling.

Cypress Grove

Trail

On this trail, you can hike to the Allan

Memorial Grove. This magnificent grove of Monterey

Cypress — one of only two natural groves remaining

in the world — is a tribute to the Allan family

which worked diligently to buy lots of the proposed

subdivision so the grove could be saved.

|

|

Page Four

|

|

Garrapata

State Park

7 miles south

of

Carmel’s Rio Road

Garrapata State Park has a

wonderfully scenic stretch of coastal area that

lures Big Sur travelers to stop and visit.

Garrapata is only 7 miles south of Carmel Valley

Road and 14 miles north of Andrew Molera State

Park. Many visitors take time to linger a bit,

enjoying the classic Big Sur shoreline here with

its rugged rocks, waves surging and crashing, kelp

beds undulating, sea lions barking, gray whales

migrating, seabirds diving and wildflowers

thriving. However, many fewer visitors know about,

nor take the time to hike, the marvelously

rewarding trails of Garrapata State Park. There are

two longer inland trails on the east side of

Highway One and also an easy, 2-mile loop trail

along the coastal bluffs.

|

|

Rocky Ridge

Trail

A rustic, broken-down barn and large grove of

old cypress signal the stop for the trailheads of

Garrapata’s inland trails. The northernmost one is

the Rocky Ridge Trail, on which energetic hikers

have options, including a 6 mile out-and-back

outing, or a 4.6 mile loop which returns via

Soberanes Canyon Trail. Hikers choosing to begin

the loop via the Rocky Ridge Trail can start along

the trail behind the barn, crossing willow-lined

Soberanes Creek, then going a short way to the

Soberanes Canyon Trail junction (which turns

right). At that point the Rocky Ridge Trail is to

the left, heading north.

|

|

|

Those Rocky Ridge hikers choosing to hike in 3

miles will walk by coastal scrub up steep trails

with spectacular vistas, at first of the shoreline

and coastal Santa Lucias. In spring the grasses

host lovely wildflowers. Rugged, lichen-covered

boulders and rock outcroppings stand out among the

grasses. One overlook has a welcome bench to rest

upon. When reaching about 1,600 feet in elevation,

views of the whole Monterey Bay and coastline are

possible on clear days.

Those hiking on to Doud Peak at the end of the

trail may even view central coast peaks to the

east.

It is debatable whether or not hiking up the

Rocky Ridge Trail is the best direction to start,

since returning on the loop via the Rocky Ridge

Trail would give hikers a constant view of the

coast while descending.

|

Photo

by Margie Whitnah Photo

by Margie Whitnah

|

|

|

Page Five

|

|

Soberanes Canyon

Trail

Approaching the Soberanes Canyon Trail from the

Rocky Ridge Trail brings the hiker’s perspective

from a broad, almost 360-degree view of the

northern coastal Santa Lucia range, with hillsides

folding and rolling toward the sea, to a narrower

perspective as one drops into the watershed of a

redwood-filled canyon. The steep trail quickly

descends an elevation of 1,200 feet from the Rocky

Ridge Trail to the canyon of majestic Sequoia

sempervirens. Along the way, admiring wildflowers

that may be blooming or, once in the canyon, the

variety of ferns, make for pleasant hiking breaks.

The cool, bubbling creek under the redwoods, passes

by large boulders, some of which may reveal to

observant visitors, the grinding areas of

indigenous people.

Hikers can expect a variety of creek crossings

in following the trail among the coast redwoods,

tanoak, California bay, madrone, buckeye, willows,

berry bushes, and other native and non-native

plants as the hikers trek toward the coast.

Particularly noteworthy non-natives are the

dense hillsides of prickly pear cactus. The cacti

have taken on a life of their own starting from the

days early settlers introduced them into this

area.

|

|

Hiking the last part of the 3-mile long

Soberanes Canyon Trail has some other botanical

surprises in the form of calla lilies that seemed

to have spread from the historic old farm area

which was once part of a Mexican land grant, and

later part of property owned under names such as

Post, Soberanes, and Doud. After pondering the

building remains, fences, and indications of

inhabitants of yesteryear, yet another marine trail

and experiences await hikers across Highway

One.

|

|

|

Soberanes

Point (Whale Peak)

This distinctive headland, a gentle cone

peaking out of the oceanscape with a

mountain backdrop, gives one a

comprehensive and dramatic look at Big Sur

coastline. It’s a short (1 mile) trail

that winds around the peak. It goes

through several coastal botanical and

intertidal zones. It ends at a view point

on top that gives one a heart-stopping

view of the Big Sur coast.

Soberanes Point Trail begins 6.7 miles

south of Carmel’s Rio Road on Highway One.

At this point, on the east side of the

road, is the trail into the mouth of

Soberanes Canyon.

Both trails traverse expanses of

non-native plants. Two local groups, Chuck

Haugen Conservation Fund and California

Native Plant Society, along with

California Department of Parks, have

vigorously fought back the invasion of

invasive species and the area is slowly

returning to a native state.

|

|

Photo by Margie

Whitnah

|

|

Whale Peak

Soberanes was used during summer by Rumsens (a

subgroup of Ohlone) and other Native Californians.

Their diet consisted of mussels, abalone, sea

lions, deer, rabbits, acorns and buckeye seeds.

|

|

Photo

by Margie Whitnah Photo

by Margie Whitnah

Rough boulders preside over whimsical canyons.

Crystals glisten in a mosaic of wildflowers and lush sea

blues. Quartz diorite, a type of granitic rock, sparkles

in the northern Santa Lucia Range. Rusty hewn rocks on

the ridge are intertwined with granite boulders that form

the ramparts of the coastal coves. Of the whole 90-mile

Big Sur coast, the formation and interaction of land and

sea is nowhere so poignantly portrayed as in Soberanes

Canyon.

Page Six

|

Photo by Margie

Whitnah

Pico Blanco through redwoods. Nearly 4,000 feet

high, this mountain of marble was thought to be the place

of human creation by Native Americans of the area.

|

Bird

Notes by Jeff Davis

and Don Roberson

Garrapata is home to the local breeding race of

the White-crowned Sparrow (“Nuttall’s” form).

Lazule Bunting and Orange-crowned Warbler are

present during summer, and Wrentit, Spotted Towhee,

and Bewick’s Wren are present year round.

|

This can also be a good place for viewing

Brandt’s Cormorant, Pelagic Cormorant, and Pigeon

Guillemot. The trail inland along Soberanes Creek

can be good for migrant vireos and warblers.

Costa’s Hummingbird, Rock Wren, MacGillivray’s

Warbler, and Black-chinned Sparrow have bred within

Soberanes Canyon.

|

Page Seven

|

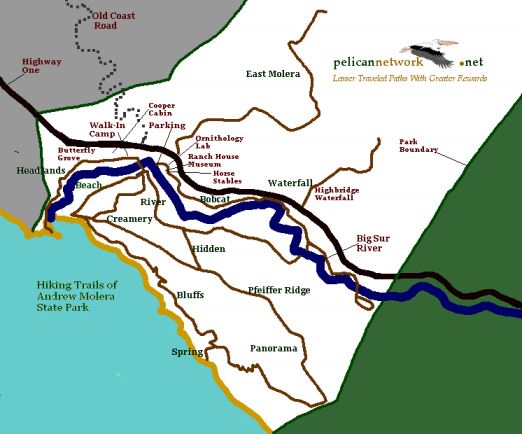

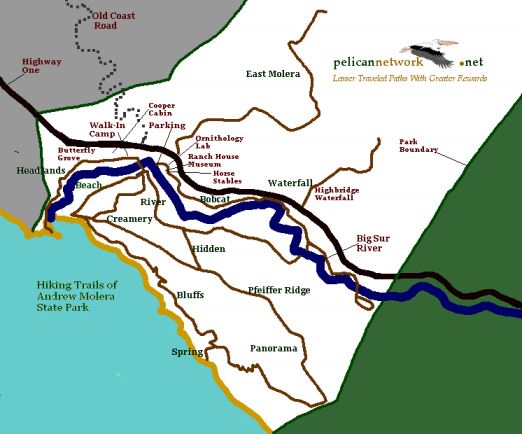

Andrew

Molera State Park

21 miles

south of

Carmel’s Rio Road

|

Seven and a half square miles of wilderness,

along the ocean, into the mountains, and complete

with a wild and scenic river – Andrew Molera State

Park is a great favorite for outdoor enthusiasts.

The entrance is three miles south of Point Sur and

4.5 miles north of Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park. An

$8 per car fee is collected at the parking lot

entrance. Guests at the Big Sur Lodge have free

entrance to all Big Sur coast state parks during

their stay at the Lodge.

A variety of interesting trails, most with

incredible views, and a 24-site walk-in campground

make Molera an engaging place to stay awhile.

The park is dissected by the Big Sur River. Long

stretches of marine terrace, vast sweeps of beach,

expansive scapes of wildflowers, hillsides of

coastal scrub, and deep old-growth redwood and oak

forests make Molera an imagination-bending

experience.

|

|

|

How the pristine Big Sur River winds from the

Ventana highlands to the sea is a rare California

natural prize. Big Sur River has no dams, nor any

man-made diversions. It is thoroughly untamed and

wonderful, it is instructive and magical all at

once. How it enters the Pacific at the Headlands is

a raucous and lovely place. This is one of the

liveliest wild bird encounters on the whole Pacific

coast. And, all along the river you walk among one

of the most precious and populated songbird

habitats anywhere.

Molera is a treasure, and there are many trails

inviting you in. Among its many attributes, it is a

very rewarding birdwatching area.

Across Highway One from the Molera entrance, the

10-mile Old Coast Road begins its backcountry wind

to the Bixby Bridge through a redwood forest.

|

|

Photo by Margie

Whitnah

Page Eight

|

|

Headlands

Trail

From the north end of the Andrew Molera parking

lot, the Headlands Trail winds along the north bank

of the Big Sur River.

This trail is a treat of diversity. It gives you

great looks into ancient, huge and wondrously

twisted oaks, into the sparkling river; a large

meadow with quail, deer and a dispersed campground;

views of Pico Blanco; a mid-1800’s homestead cabin;

a winter Monarch Butterfly habitat in a large blue

gum eucalyptus grove; riparian forest of alders and

willows; sea stacks called Sur Breakers here and

home to cormorants; extensive kelp forests; river

lagoon home to large colonies of ducks, sea and

shore birds; and, lovely headlands with many Indian

middens.

Along the lower Big Sur River, the trail offers

rare encounters with many bird species: chickadees,

bushtits, warblers and many other songbirds, belted

kingfishers, red-shouldered hawks, kites, kestrels,

and golden eagles.

At the headlands there are views up and down the

coast and to the mountains of the Santa Lucia

Coastal Range. Offshore, California gray whales are

seen during their winter migration south to Baja

California lagoons, and Spring return to the

Arctic.

This trail is one mile, and easy. But it can be

uncomfortable when cold and windy.

Beach Trail

Loop

An easy, nearly 2-mile walk along the Big Sur

River through riparian thicket, along a vast and

fascinating beach and back through a bird watching

paradise in a restored meadow.

|

Photo at right: Bluffs

Trail seen from above Big Sur River lagoon at Headlands

Trailhead.

|

|

Creamery

Trail

Return by reversing to the Creamery Trail junction.

Once a milk cow pasture, the meadow is being

restored to its native state by the California

Department of Parks. It’s a massive job to

revegetate the meadow with native plants, but the

progress to date is inspiring.

In this trail loop you might see bobcats and

coyotes, and probably will see lizards, rabbits,

and deer.

Beginning at the parking lot area’s picnic site,

cross the river at the footbridge, which is

constructed annually before Memorial Day and

removed after Labor Day. Beach Trail begins on the

right at the trail fork. Follow it to the beach.

Before reaching the beach the Creamery Trail

junctions with the Beach Trail. Continue on to

experience one of California’s most scenic and

dramatic beaches. Molera Beach spans 2.5 miles from

the Headlands at the Big Sur River lagoon at the

river’s mouth, south to Cooper Point.

To the north there are whimsical collections of

driftwood, and great waves to the south. It is

beautiful.

|

Photo

by Jack Ellwanger Photo

by Jack Ellwanger

|

|

Page Nine

|

|

Ridge, Panorama,

Spring and Bluffs Trail Loop

For those wanting a full day hike with

incredibly diverse sights, flora and elevations,

taking a loop hike which includes these four Molera

State Park trails will guarantee a memorably

rewarding outing.

This loop hike, in the neighborhood of 8 miles,

can be done in either direction, but this

description will follow in order the Ridge,

Panorama, Spring, and Bluffs Trails. The loop can

also be started from various places in the park,

but this description assumes that hikers will start

near the northwestern end of the Ridge Trail

(closest to Molera Beach). Trails that meet at,

near, or en route to the Ridge Trail junctions

include: Beach and Creamery Meadows loop trails and

the Bluffs Trail. Looking at a map, hikers will

also note that about a third of the way up the

Ridge Trail, the Hidden Trail, runs into the Ridge

Trail, providing yet another option.

To begin this loop hike, hikers need access to

the trails on the park’s more southern, coastal

side of the Big Sur River. Many months of the year,

hikers can do this hike by crossing the Big Sur

River at the parking lot’s picnic area by using a

temporary bridge or by wading across the river if

it isn’t running too high or too swiftly. The water

can be quite chilly and the rocks in the river bed

can be more tolerable when some sort of footwear is

worn. Another way that some hikers access the

trails for this loop trip, is to cross the river by

fording it at the Big Sur River mouth. Always check

with the staff at the park’s kiosk for advice first

about the tides at the river mouth or current

safety conditions for river crossings, if the

narrow footbridge is not up.

Once hikers have navigated any waterways, walked

the earlier described “flatland” trails (Headlands,

Creamery Meadow, River or Hidden Trails) and

reached a junction of the Ridge Trail near Molera

Beach, this “four-trail” loop hike can begin.

Before starting, hikers may want to visit

Molera Beach briefly to appreciate the beauty of

the beach, waves, river mouth, headlands, coastal

bluffs and vistas. Returning to the nearby trails

that meet up with the Ridge Trail, hikers will

re-visit many of the native plants and shrubs that

were seen on their stroll from the parking lot to

the beach and bluff area.

|

|

|

The 2.7 mile Ridge

Trail starts out fairly flat, among the

splendid array of relatively low-lying vegetation

mentioned in the earlier descriptions of the park’s

river land area. As this wide trail (previously a

fire road) climbs steadily uphill, the views of

prominent peaks to the east, the coast and river

mouth become awesome. The views only diminish when

hikers begin entering the sunlight-filtering

tunnels of coast live oaks and tanoak that surround

the trail — trees full of character, gnarly with

age and weathered with moss and lichen. Soon, the

woods of oak give way to stands of towering

redwoods, as hikers ascend gradually along the

reddish duff ground cover and accompanying ferns

and sorrel.

The Ridge Trail ends at a lovely junction rest

stop complete with a bench under an old cypress,

beside a fence that marks the southern boundary of

the park. The coast views are spectacular, though

the signs along the road south of the fence are

less welcoming, “Posted: No Trespassing – Keep

Out.” New and modern, private homes with priceless

views are built here, but lovely native brush still

graces the hillsides on the north side of the

fence.

After lingering awhile, hikers will be ready for

the 1.9 mile Panorama

Trail with a welcome downhill grade and

narrow, but interesting switchbacks. The coastal

views can sometimes be so clear, it is said, that

Cone Peak, rising over 5,000 feet high, forty miles

south, can be seen. The vegetation along this open

coast have to adapt to the strong winds and salty

atmosphere, as is seen by some dense, tangled

redwood forests that survive here, not towering,

but unusually short, and seemingly huddled together

for protection from the elements.

Note: Hikers have two options for

returning to the parking area. The first is the

South Boundary

Trail, about a third of a mile from the

Panorama’s bench, which is not recommended, for it

presently is overgrown and choked with poison

oak.

The second is about a half mile further,

Hidden

Trail. Although steep most of the way,

this trail offers nice walking paths through

ancient oak and redwood groves. Before descending

to the River Trail, hikers are treated to splendid

views of Pico Blanco.

|

|

|

Page Ten

|

|

As the Panorama Trail winds toward the ocean

cliffs, a sign signals a side trail that shouldn’t

be missed, the Spring

Trail. This tenth-of-a-mile spur to the

beach goes down a delightful little gully with a

creek that leads to sands rich with animated

driftwood of all shapes and sizes. If the tide

isn’t high, hikers can often enjoy beachcombing up

to nearly a mile of shoreline between Cooper and

Molera Points. At times, the beach’s northern

bluffs host an idyllic waterfall which splashes

down onto the boulders, sand, and anyone who can’t

resist this refreshing enticement.

|

|

Hopefully refreshed by their visit to the Spring

Trail’s beach paradise, hikers can now retrace

their steps up to the

Bluffs Trail. This trail runs 2.8 miles

along the scenic bluffs back toward the mouth of

the Big Sur River along a relatively flat plane,

except for a couple gullies. The red dirt and

golden sandstone of the marine terraces are

especially rich in color if you have lingered long

enough for the sun to be setting low in the sky.

The coastal bluff grasses at dusk are muted in

color, with occasional blossoms adding interest.

Arriving to the river mouth at sunset is a mixed

blessing — the sunset setting can be overwhelming,

even sensational, but the dash back on the darkened

trails and, perhaps, an icy river crossing, can

make hikers wish they had allowed more time to

return to the parking lot or their campsite! But

whatever route or amount of time hikers choose to

use, the rewards of this Molera day hike loop are

really great.

|

|

East Molera

Trail

Big Sur travelers passing along Highway One by

Andrew Molera State Park must often be impressed by

the view of a majestic, white peak which rises to

the east. They aren’t surprised to learn that it is

named, Pico Blanco, which is Spanish for “white

peak.” Hikers along the well-trodden Molera trails

to the west of Highway One also can’t help but be

awed by this huge mountain that seems to reign over

the whole area. Many Molera visitors may have mused

about hiking up that stark, marble peak, but that

peak hike is a tough, dry and long trail climb.

Most Molera hikers don’t know that a trail on

the east side of the highway is a nice compromise

for those wanting to view Pico Blanco from a

closer, higher location. The route is via the East

Molera Trail which is either a 3.2 or 3.8 mile

out-and-back hike, depending upon the starting

point. Or, it can be a little longer for those

wanting to take a side spur trail across a gully to

a lovely, old oak on a knoll.

Starting from the Molera State Park parking lot,

hikers walk an extra .3 mile by going down the

service road past the ornithology lab, the stables,

and then paralleling the highway, through an

under-road culvert and onto a dirt road.

|

|

|

|

Shortly, they meet up with the trail heading

left up the hill from the alternate trailhead

option. Hikers starting from the Highway One

trailhead, can park in turnouts not far from the

old, wooden cattle chute, which forms a gateway to

the trail.

The first six-tenths of a mile or so are a

fairly steady slope through gnarly coastal live

oaks and bay laurels, while further along redwoods

line the gully off toward the right. To the left,

the hills’ slopes are covered with grasses which

may be golden in some seasons or, during others,

lush green with large orange and purple patches of

wildflowers. Rest stops along the slopes, reveal up

close to hikers that there is a wide spectrum of

colors and types of flora to be discovered

here.

Near a wooden fence, where the trail angles off

to the left with a significant climb for the next

mile, hikers may choose to take the time to take a

short side spur to the right. Those taking the spur

will be passing by redwoods rising from a narrow

canyon, stepping over the small creek and up a

knoll, but not too far, to the trail’s end at a

lone, stately oak. It’s a serene place to enjoy the

views, eat lunch or just relax in the tree’s

shade.

|

|

Back at that fence where the trail goes left

climbing 1,000 feet in a mile, hikers encounter

switchbacks and slopes of between 20-30% grade, but

the rewards from the views also increase

dramatically. Hiking up the mountain’s ridges

toward a saddle that is crested with stands of

redwoods and neighbored by Pico Blanco looming in

the not-so-distant background, gives hikers

motivation to continue to the 1,549-foot elevation.

Besides all the trailside attractions of

wildflowers, insects, lizards, and native plants,

the awesome, far-off attractions of soaring birds,

perhaps condors, Point Sur, Molera headlands and

beach, may take the hikers’ mind off the physical

effort.

|

|

Bird

Notes by Jeff Davis and Don

Roberson

Molera State Park is the premier birding

locality in the region and offers good birding at

any season. In 1999 it was designated a Globally

Important Bird Area by the National Audubon

Society-California, the American Bird Conservancy,

and California Partners in Flight. It is best

birded by taking the one mile trail on the north

side of the Big Sur River from the main parking lot

to the beach.

The area is excellent for woodpeckers,

flycatchers, vireo, and warblers. Most records of

rare and unusual birds for the region have come

from this site.

This is also the home of the Big Sur Ornithology

Lab which operates a constant-effort mist netting

and banding station about1/8 mile upstream of the

main parking lot.

|

|

|

Page Eleven

|

|

|

Pfeiffer

Big Sur

26 miles south

of

Carmel’s Rio Road

$8 Park entrance fee per car

Plenty of picnic sites along the Big Sur

River

|

Pfeiffer Big Sur

State Park was established in 1933, and is the

most popular park on the Big Sur Coast. There

are more than 200 drive-in tent camp sites with

tables, fire pits and cooking grills in the

redwoods and along the Big Sur River, an

exciting complex of trails, and an interpretive

nature center. The campground has hot showers

and restrooms, large group campgrounds, campfire

center, store, laundromat, and Park Rangers

conduct daily nature programs during the summer.

Make reservations through 1-800-444-7275. There

are 62 modern, woodsy, cottage units in the

redwoods at the Big Sur Lodge in the park. Call

831 667 2025 – or visit:

www.pelicannetwork.net/bigsur.lodge.htm

|

Pfeiffer Falls

Photo by Jack

Ellwanger

|

In Big Sur River Valley,

from Pfeiffer Ridge, which flanks the ocean, to the

Ventana Wilderness, Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park is a rare

and wonderful place.

It is the heart of Big Sur –

where the first American pioneers settled.

It was the most hospitable place

– river, valley, redwoods. Settlers farmed and made honey

with the abundance of wildflowers.

The park is 1,006 acres of old

growth redwoods, magnificent mountain views, granite

river gorge, condors and rich history.

|

|

Pfeiffer Big Sur State

Park is a hiking paradise. Within the park itself

there are almost 11 miles of trails of varying

degrees of difficulty. From the short Nature Trail,

to the vigorous mountain trails into the

magnificent Ventana Wilderness, there is a

bountiful variety of trails. One of the most

popular trails follows Pfeiffer-Redwood Creek to

the 60-foot high Pfeiffer Falls and features

exceptionally fine redwood groves.

|

|

Pfeiffer Redwood

Creek Trail to the

falls is through a lively, dense old redwood grove.

It is an instructive trail. You can see how a

redwood forest makes its own soil and understory.

The creek cuts through alluvial deposits, and you

can see how the valley built up over the

eons.

|

|

|

Pfeiffer Falls

Trail

This 40 to 60 minute stroll along Pfeiffer Redwood

Creek features some of the finest redwood groves in

the Big Sur region.

Expect steps in the steeper sections and a

number of scenic bridges across Pfeiffer Redwood

Creek.

|

|

The 60 foot high waterfall at the end of the

trail is a scenic highlight. A wooden platform at

the base of the falls is a fine place to rest,

meditate or have a picnic lunch – 0.7 mile one-way

from the Lodge.

|

|

|

|

Page Twelve

|

|

Nature

Trail

This self-guiding trail can be toured in about 30

minutes and is a 0.7 -mile round trip from the

Lodge. The trail offers a fine opportunity to see

many of the plants that are native to Big Sur.

Printed nature guides are available at the western

end of the trail, between the Lodge and the Ranger

Station. Suitable for wheelchairs.

|

|

Valley

View

From either the beginning of the

Pfeiffer Falls trail, or from the base of

the falls themselves, you can climb

through the oak woodland to Valley View

Overlook. The view from this vantage point

includes much of the Big Sur Valley, Point

Sur and Andrew Molera State Park. The

outlook is a mile one-way from the Lodge

and 0.5-mile from Pfeiffer Falls.

Oak

Grove

The great beauty of Big Sur is due in

part to the variety of its natural

ecosystems. The Oak Grove trail

exemplifies this as it travels through a

number of plant communities.

From deep redwood groves to open, oak

woodland, and to hot, dry chaparral, this

60 to 80 minute hike makes it possible to

enjoy the many different faces of Big Sur.

It is approximately 3 miles round trip

from the Lodge.

Big Sur

River Gorge Trail

The wild and scenic,

completely untamed, Big Sur River begins

high in the Santa Lucias by the Ventana

Cones. It drains more than sixty square

miles of raw coastal mountain watershed

and plunges down a narrow granite gorge

into the park and lazes toward the

ocean.

Huge boulders brought by the river are

flung around the canyon in great artistic

array. Pebbles brought down the undammed

river provide spawning and rearing habitat

for steelhead, a seagoing trout. Sands

brought by the river spread out along the

banks by the redwoods making a unique and

pleasing scene.

Photo

by Jack Ellwanger

Manuel

Peak

At the top, you will get one of the

loveliest, sweeping views of the Ventanas.

Getting there will test your conditioning,

though. This steep, one way trail, is more

than 5 miles, averaging nearly 12%

gradient, rising more than 3,000 feet.

Plenty of ticks and poison oak.

|

|

|

Photo

by Margie Whitnah Photo

by Margie Whitnah

|

Buzzard’s

Roost

A moderate two-hour hike along the Park’s

western edge will take you along the river, through

shady redwoods, then through a series of

switchbacks among bay trees and tan oaks to the

chaparral-covered top of Pfeiffer Ridge.

Photo by Margie

Whitnah

Up there is a magnificent panoramic view of the

Pacific Ocean and the Santa Lucia Mountain Range.

Interestingly, on the ridge redwoods grow alongside

chaparral plants. The unusual soils made of

sandstone and shale, and the rare microclimate

formed by the cool ocean breeze mixing with the

warm valley air, create a fascinating array of

plants – dwarf redwoods with chamise, wheat leaf,

ceanothus, yerba santa and manzanitas side by

side.

The entire Buzzard’s Roost loop is a 5-mile

round trip from the Lodge.

|

|

Photo by Margie

Whitnah

Big Sur is

Condor Country

The whole Big Sur Coastal range is great condor

habitat. Hikers can expect to see these avian wonders

from most trails. Recently, condors began feeding on

deceased marine mammals. This provides an excellent

clean-up service, and is an important resumption of their

historic feeding practice. Marine mammals killed by

orcas, or dead by natural causes are dietary favorites.

All condors in the Big Sur region have been reintroduced

by the Ventana Wildlife Society. The last 15 in this

region were captured in 1985. Now there are more than 26

here. They were bred in captivity. Three pair are

nesting, and one produced a chick in the Spring of 2007.

It is the first condor chick born in the wild in more

than 100 years.

Page Thirteen

|

|

Page Fourteen

|

|

Page Fifteen

|

|

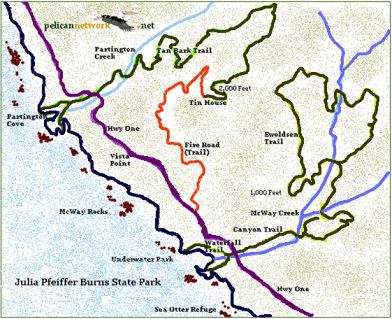

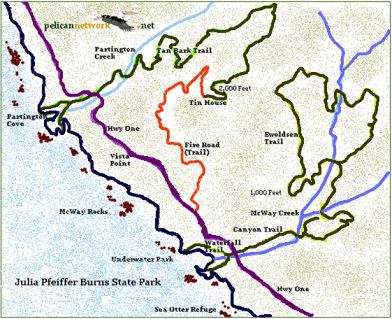

Julia

Pfeiffer Burns

37 miles south of

Carmel’s Rio Road

$8 Park entrance fee per car

Plenty of picnic sites along the Big Sur River

Almost

2,000 acres of coastal, canyon and mountain greatness, Julia

Pfeiffer Burns State Park is a fantastic place and a perfect

introduction to Big Sur.

Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park is 11 miles south of

Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park on Highway One and covers 7

miles of exquisite coast with many coves.

Within the park are idyllic trails, waterfalls,

underwater parks, historical gems, riparian hardwood

forests, mystic redwood groves with ancient growth trees,

and deliriously beautiful scenery.

|

McWay Falls

Trail – A short walk through a tunnel

and along the cliff of a cove to the Brown’s

Waterfall House site. Entrance to Julia Pfeiffer

Burns McWay Falls Trail is 11 miles south of The

Big Sur Lodge and Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park on

Highway One.

|

|

Canyon Trail

– A third-mile walk into old growth redwoods

to waterfalls of the South and North Forks of McWay

Creek.

|

|

Ewoldsen Trail

– A 4.5-mile loop hike through old growth

forests to the top of the coastal range.

|

|

Partington

Cove – A steep trail to a tunnel and a

historic cove, and also to the big rock beach where

Partington Creek enters the sea.

|

|

Tan Bark Trail

– A 3.2-mile hike through ancient forests,

mountain springs to a mountain top with spectacular

views of the coast- a 6.4-mile round trip

hike.

|

|

Canyon Fall

Photo by Jack

Ellwanger

|

|

Canyon

Trail and

Ewoldsen

Trail

A 4.5-mile steep hike to the top of the

Coastal Range.

From its beginning at the parking area

of Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park, the trail ascends along

the McWay Creek through a redwood-forested

canyon.

The Canyon Trail continues beyond the

intersection of the Ewoldsen Trail. At its end you face a

high waterfall, an ancient redwood embracing a large granite

boulder and steep canyon walls graced with ferns.

The Ewoldsen Trail ascends the canyon before the Canyon

Trail’s waterfall. For the first half of the trail you walk

along McWay creek in a water wonderland with many water

cascades.

The trail is well-marked, is

well-maintained, and excellent bridges cross the creeks.

After a mile up the trail, you encounter a two-mile loop.

After a quarter mile along the Canyon

Trail, the Ewoldsen Trail intersects the Canyon Trail, then

branches off to the right and up slope.

It maintains a steady ascent out of the

canyon, crosses creeks deep in redwood forests, rises

through sunny oak and chaparral scrub. At times, you’ll see

lots of butterflies and wildflowers.

Ewoldsen Trail is a deep,

quintessential Big Sur watershed experience.

Evidence of the wondrous powers of

regeneration is all around the hiker for most of the trail.

|

McWay

Falls and Saddle Rock McWay

Falls and Saddle Rock

Photo by Jack

Ellwanger

Page Sixteen

|

Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park

experienced a massive slide that disconnected

the Tan Bark from the Ewoldsen Trails. There are

no immediate plans to re-connect the trails.

|

Ewoldsen Trail often crosses McWay Creek’s North

and South Forks and their tributaries.

|

This park is a favorite condor viewing

area.

|

|

Page Seventeen

|

|

Page Eighteen

|

|

|

The Partington

Canyon watershed

showcases the distinctive riparian woodland of

Central California’s coastal watersheds. The summer fog

forms from the clash of warm land air and cold water

upwelling from deep offshore canyons.

Partington Creek frolics rambunctiously around huge

boulders, pools, rapids and cascades. Giant sycamores and

redwoods regally congregate around seeping, bubbling

springs.

|

Partington

Cove

Partington has two

great hikes. First, is a two-mile loop to the

ocean. It begins at an iron gate along Highway One

– nine miles south of Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park,

and 35 miles south of Carmel’s Rio Road.

It is a fine trail down to the

beach, but steep. The trail goes down to the

Partington Creek’s graceful little exit to the

Pacific Ocean. Then you back track up the creek to

a bridge (there’s an outhouse nearby). Over the

bridge you soon come upon a 100-foot tunnel to

Partington Cove.

|

|

|

This is like Fantasy

Island, only better, as this is real. Mules used

to haul wagons of tanbark through here.

|

|

The picturesque little cove is

home to sea otters and seals, very clear waters and

a kelp forest. It is a wildly aquatic experience.

On the point is an old hoist stanchion, formerly

used for loading cargo, lumber and tanning bark.

The iron eyes for tying up the ships are still in

place. You can imagine pirates and bootleggers

rousting about.

|

|

Pacific sunset seen at Partington

Page Nineteen

|

Tan

Bark Trail

|

The second Partington hike begins on the east

side of Highway One. Bring drinking water and maybe

also a flashlight, just in case. For the first

third of the trail there is plenty of good fresh

water. Not so, later.

Initially, the trail can be confusing. If you

start out going to the left of the creek, you will

have a lovely saunter in the redwoods, and come

upon an idyllic picnic spot — a boulder hanging

over a wide sparkling pool, with a waterfall in a

cathedral of Sequoia sempervirens. But, this

is the wrong trail. It dead ends at a cliff.

The real trail, the Tan Bark, goes along the

south side of Partington Creek, and then up. It

branches to the left in three spots, leading into

forests deeper within the canyon. It stays right,

ascending the canyon. There are a few signs. The

Old Coast Trail crossed here, and surely the ghost

of poet Robinson Jeffers is about.

The trail follows a 2,000-foot rise in elevation

over 4 miles through a redwood canyon.

Then the Tan Bark Trail climbs along a roaring

stream, waterfalls, springs bubbling out of

hillsides, and into thick stands of exotic oaks,

venerable madrones and manzanitas.

The McLaughlin Memorial Grove, on a ledge in a

nook of the forest, high above the raucous creek,

is awesome. The Grove is home to redwoods with

spiraling bark.

In several places, particularly farther uphill

in the Swiss Camp area, you see arduous stonework

made 80 years ago. Gunder Bergstrom, who lived here

in the 1920s, did the work, and it shows a deep

love for the area. The stone bridge he built is

like a little human cameo to accent a wish to

preserve one of nature’s finest settings. The

bridge allows the place to be appreciated and

protects the stream environment from human

impact.

|

|

|

You cross

streams and pass springs that bubble up in fern

groves, and out of the sides of the canyon. The

trail switches back into sycamore, then tanoak and

into unusual old growth redwoods.

The trail

hugs the canyon slope which is chaparral-studded

with colorful madrones and manzanitas and piercing

views of the sea, across to Partington Ridge, and

up into the Santa Lucias. You ascend on a

moderately steep gradient, about 12 to 14%,

continuing up until you are 2,000 feet above the

ocean, and can see it through redwoods. It looks

like another planet. On summer afternoons you can

watch huge fog banks flow toward the shore far

beneath.

Near the

top you encounter a well-graded road. This can be

your return trip. It is considerably shorter,

descending to Highway One about three-quarters of a

mile south of the point at which you started. So,

you will have to hike up the highway to get back to

your car.

Up here you feel you are at the top of the

world. From here the coastal views are sweeping and

the sea is endless. The view east is to the Santa

Lucia high country.

You find the Tin House at the top. It was built

by Lathrop Brown, who lived in the grand home

across the cove from McWay Falls. Brown was a high

official in the U.S. State Department during

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency. Oddly, the

house up here was built of tin salvaged from gas

stations before World War II. Its design is

strange, too. Even though the Tin House is situated

atop a 2,000-foot mountain, practically on top of

the ocean, with unobstructed, majestic vistas, it

has no view from inside the house to the west.

|

|

|

Page Twenty

|

|

Limekiln

State Park

What fascinating and rewarding experiences this

state park readily offers in the heart of Big Sur.

Limekiln State Park is located 36 miles south of

Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park, centered two miles

south of Lucia and two miles north of the eastbound

Nacimiento-Ferguson Road turnoff.

Visitors of almost all ages will delight in

wandering the short, fairly easy trails, while

being awed by the stately redwoods, free-flowing

creeks, a royal waterfall, historic limekilns, and

an enjoyable stone beach. Longtime lovers of

natural and cultural history may find themselves

enthralled with this park, and even the uninitiated

might, too, getting their feet wet, perhaps

literally with creek crossings.

Visitors with foresight may arrange to camp in

one of the 33 campsites for an overnight or

extended stay. Others with less time available can

easily explore the four highlighted areas in a

couple hours time, covering less the “less-than a

few” total miles on the relatively level

trails.

After driving down the short eastbound road from

the south end of the Limekiln Bridge on Highway

One, there is day-use parking available and also

restrooms. Most visitors may prefer to head

northeast up Limekiln Canyon, hiking out through

the campgrounds to the three redwood-lined trails.

Doing that, leaves the fourth destination, Limekiln

Beach, for last.

Though children may imagine themselves to

exploring uncharted redwood groves and creeks, they

can be reminded that long, long ago, as difficult

as it was to access these intimidating canyons and

cliffs, indigenous people were able to inhabit or

visit these formidable areas. By the 1800’s,

foreign explorers, hunters, hardy American pioneers

and homesteaders managed to journey here by trails,

too. Some were drawn by the natural resources,

particularly the timber and the extracting of

limestone to manufacture lime, used to make cement.

In the late 1800’s, the area near Limekiln Beach,

Rockland Landing, was a vital hub of activity for

materials and goods coming and going on

schooners.

|

|

Limekiln

Trail

At the end of the campground area, the trail

leads to a wooden bridge which crosses Hare Creek.

(Lou G. Hare, 1867-1921, was an early Monterey

County Surveyor.) After crossing the bridge, one

soon comes to signs designating the Hare Creek

Trail going to the right along Hare Creek (0.3

miles), the limekilns (0.5 miles) and Limekiln

Falls (0.4 miles).

Since this trail description is intended to lead

to the kilns, one can stay to the left following

Limekiln Creek’s West Fork until reaching the

junction where Limekiln Falls Trail and Limekiln

Creek meet. Staying to the left on the trail to the

kilns, one goes about a third of a mile until

reaching a fenced-in area which reveals four

towering brown steel limekilns, with their ovens

and stonework at their bases. In the heyday of

Rockland Lime and Lumber Company, cut redwoods went

into the ovens to heat the fires, as limestone and

firewood were put into the top. That purified the

lime by a process known as slaking or calcining, by

using slow, regulated burning to produce the lime.

Then, the slaked lime was shipped in barrels to San

Francisco or Monterey for cement-making, among

other uses. The kilns are now roped-off for

visitors’ safe viewing.

|

|

Limekiln Falls

Trail

Retracing the trail along the Limekiln Creek’s

West Fork brings hikers back to the junction with

main stem of Limekiln Creek where a sign points the

way to Limekiln Falls. Depending upon the water

level, pant legs may need rolling up and water

sandals may prove useful, since this next quarter

mile or so will involve several creek crossings,

including some with footbridges.

Limekiln

Falls Limekiln

Falls

Photo by Margie

Whitnah

|

|

Limekiln Falls during

drought

Photo by Jack Ellwanger

But the steps, crossings, and any wet shoes will

be well worth the adventure, especially when the

fall’s roar comes into earshot and then the

spectacular 100-foot waterfall spilling over the

limestone cliff comes into view. Even the

refreshing mist can be a bonus. Once rested and

ready, the trail and creek crossings can be

carefully retraced, returning to the sign at the

third branch of these canyon hikes, “Hare Creek –

.3 miles.”

|

|

Hare Creek

Trail

Hare Creek trail visitors follow along the left

side of Hare Creek while hiking to its “End of

Trail” sign beside a fallen redwood log. The canyon

walk follows along the charming Hare Creek and its

pools which sometimes are home to steelhead. The

redwoods host sorrel, ferns, and other delightful

vegetation in their moist, fragrant, shadows.

Hare Creek Trail

Photo by Jack

Ellwanger

At the end of the Hare Trail, by a rock wall, a

cascade under a fallen redwood flows into a broad,

fern-rimmed pool. It’s a wonderful place to rest

and appreciate Mother Nature before hiking back

along the trails to the campground and out to

Limekiln Beach.

Pool and fall at end of Hare Creek trail

Photo by Jack

Ellwanger

|

Photo by Margie

Whitnah

|

Limekiln

Beach

Limekiln Beach, located under the Highway One

bridge, is accessed by hiking out the dirt road,

just west of the campground and parking lot. One

can stroll a long way following the curve of the

beach on the sand and rounded stones, trying to

imagine the busy shipping port of yesteryear,

Rockland Landing, with its barrels of lime going

out and commercial supplies coming in. Or, maybe

one can just watch the ocean waves going out and

coming in, as children on the shore are dreaming up

their own stone structures and cementing them with

sand.

|

Ancient redwood remnant along Limekiln Creek

By Jack

Ellwanger

|

|

Page Twenty-One

|

|

Big

Sur History

Big

Sur

began 35 million years ago, 14 miles deep in the

earth off the coast of Mexico. Tectonic plates

rubbing against each other moved these mountainous

rocks north. Five million years ago they pushed up

out of the ocean to form an island that is now Big

Sur. The Santa Lucia range, which includes the

Ventana Wilderness of today, is young and

precocious.

Indians

Before colonization by the

Spanish Empire, indigenous people populated the

southern Monterey Bay area including the Salinas

Valley, Monterey Peninsula, Big Sur coast, and

Santa Lucia Mountains. Throughout the years, these

people have been identified by different tribal

names including Ohlone, Costanoan, and Esselen.

Their descendents today chose a legal name that

reflects that identification diversity.

Today, the Ohlone/

Costanoan-Esselen Nation is seeking federal tribal

recognition.

The Esselen territory

encompassed the interior of the Santa Lucia Range

and portions of the Big Sur coast. The Spanish

colonization and mission building was to change

every aspect of indigenous peoples’ lives in

California, and the Monterey area was no exception.

The forced relocation of Native Americans decimated

their culture and numbers. In 1939 the last fluent

speaker, Isabel Meadows, of the traditional local

languages died.

But the culture and people

survived and thrive today. Some Esselen escaped the

missions and hid in caves in Carmel Valley. A few

became trappers for Russians, later cattle drivers

for the Spaniards.

Some re-entered American

society as Mexicans. These few have kept their

Native American traditions alive, and continue as

stewards of the Santa Lucia Mountains and coastal

valleys. Salinan Indians thrived in the San Antonio

Valley, Salinas Valley and throughout the Santa

Lucia range from Carmel Valley to Paso Robles, and

to Morro Bay on the coast.

|

|

|

Before the arrival of

American pioneers, the Big Sur region was settled

during the Mexican period.

The development of two

very large land grants from the 1830s, El Sur and

San Jose y Sur Chiquito, were north of the park but

led to settlement farther south. The culture of the

coast during the nineteenth century was

predominantly Hispanic. To this day, an Hispanic

thread continues to weave throughout the area’s

history and culture.

|

|

The first European

immigrants to settle permanently in Big Sur were

Michael and Barbara Pfeiffer. Their son, John, and

his wife, Florence, homesteaded a parcel on the

north bank of the Big Sur River. Like most settlers

of that era, they spoke Spanish. John was more

comfortable speaking Spanish than

English.

When John and Florence

Pfeiffer settled the area, they found that others

were drawn here by the fishing, hunting and

exploring. The Pfeiffer’s let the visitors stay at

the ranch. John cared little for money and insisted

that visitors not be charged.

Florence, however, became

increasingly disgruntled by the number of drop-in

visitors, the cost and workload she bore for their

care, and the rudeness of those who took the

Pfeiffer’s hospitality for granted.

Finally, her patience

reached its end when she saw a visitor beating his

mule. She told the bully, who had stayed without

even a “thank you” to the Pfeiffer’s, that he

couldn’t treat the mule like that on her property.

From that time on, visitors had to pay for their

meals, beds and horse feed, and were forbidden to

mistreat an animal. John was disappointed about

charging guests, but acquiesced to his wife’s

wishes. That was the beginning of the Pfeiffer

Ranch Resort, now the location of the Big Sur

Lodge.

In 1933, the Pfeiffer’s

sold and donated 680 acres of their ranch to the

State of California. This became Pfeiffer Redwood

State Park in commemoration of the family’s

contribution to the pioneer history of the Big Sur

region and of their gift to the state. Like most of

the Big Sur settlers, John Pfeiffer was a

naturalist and conservationist, and he stipulated

that the ranch be saved as a park.

|

|

|

Page Twenty-Two

|

|

|

Getting

Around Big Sur

|

The most

asked question by visitors is, “Where is Big Sur?”

The answers usually are, “It is a region 90 miles

long and 40 miles wide;” and, “It is not a place.

It is a state of mind.”

However you

like to refer to this unique slice of geography,

Big Sur is a rare place with many faces.

|

Like an

island, the northern half of the Santa Lucia coastal

mountain range has evolved an unusual ensemble of

geologic and botanical communities. Nearly 200 plants

have their northernmost habitat here, and, similarly,

nearly that many have their southernmost habitat here

also. You will see Yucca Whipplei from the Mexican

high desert, and Sequoia sempervirens from the

subarctic peacefully and luxuriantly prospering here.

|

Today,

Big Sur is a coastal wilderness. It is as

pristine as could be imagined for its 200,000

acres and 90 miles of premium California coast.

It is a grand testimony to the human craving for

appreciating this raw, bold beauty that it has

been protected. A highway was constructed in the

1930’s just to see this boldly beautiful natural

setting. The road in this setting has come to

define Big Sur for most people. But, the will of

the pioneers to conserve the remarkable region

has prevented Big Sur’s destruction by

development.

|

|

Margaret

Owings,

who created Friends of the Sea Otter, said,

“There’s something about Big Sur that puts

people in their place. Something they have to

come back to, because it does something to you.

And it gives you a responsibility to keep it

like this.”

Ninety-five

per cent of Big Sur is the fold-upon-fold of

Ventana Wilderness, each a unique watershed,

rare biology, incredible geology that most

people never see. In the coastal mountain

canyons that vein the intricate quilt of

watersheds, such as seen when hiking the

Partington watershed, one gets an inside peek at

this wondrous country.

In

Pacific Ocean coves, sea otters and elephant

seals have been rediscovered after their

announced extinction.

You can

access nearly every distinctive habitat here

from Highway One. The U.S. Post Office, sort of

the “official” location of Big Sur, is two miles

south beside an interesting assortment of

businesses.

|

People

of Big Sur

Some of the

finest novelists, painters, poets and photographers have

found inspiration for their works in Big Sur’s Coast.

Robert Louis Stevenson, Mary Austin, Jack London,

Sinclair Lewis, John Steinbeck, Robinson Jeffers, Lillian

Bos Ross, Jack Kerouac, Henry Miller, Edward Weston,

Ansel Adams all came here and enriched their

palettes.

For intellectual

stimulation and a literary orientation of the meaning of

Big Sur, visit the Henry Miller Memorial Library. You

will find it in a redwood grove through an Alice in

Wonderland rabbit hole four miles south of the Big Sur

Lodge. The director, Magnus Toren, speaks many languages,

has sailed around the world, and keeps a provocative

bookstore.

|

|

Page Twenty-Three

|

|

Pfeiffer

Beach hosted

movie stars

|

Pfeiffer

Beach, where Richard Burton and Elizabeth filmed

Sandpiper and where Burt Lancaster and

Deborah Kerr filmed their famous beach scene in

From Here to Eternity, is 3.3 miles from the

Big Sur Lodge. Drive south (and up the hill) 1.1

mile to Sycamore Canyon – the road is not marked.

There is a sign that reads, “Narrow Road – RVs and

Motor Homes not recommended.” Turn right and slowly

drive two miles all the way through the canyon to

the U.S. Forest Service parking and restroom

facility. Pay $5 per car.

|

|

Photo by Margie

Whitnah

Pfeiffer Beach

photographed in 2001 when outrage around the world

followed news of the U.S. Navy intent to use Big Sur as a

practice facility for jet fighter bombing.

Page Twenty-Four

|

|

Wildflowers

and Native Plants of Big Sur

Big Sur’s

mild climate, rare geology and isolation conspire

to provide habitat for a great diversity of plant

communities. Almost half of all plants in

California have a home here. Many plants have their

only natural home here. Nearly 200 plants have

their southernmost or northernmost home here.

|

Indian Paint

Brush

Photo

by Margie Whitnah

|

|

|

Our area of

the Pacific Ocean is transitional between the

Southern California and Oregonian zones. Water

temperatures vary by the influence of each zone and

the deep underwater canyons.

|

|

Cold water

from deep offshore canyons wells up to meet warm

air and create vast fog masses.

|

Yucca

whipplei

|

|

|

Page Twenty-Five

|

|

Redwoods

Redwoods

thrive here because of the

fog.

They grow on the

valley floor along the river, and on the north

facing slopes. Along the streamway grow

cottonwoods, white and red alders, western

sycamores, big leaf maples and tall willows. Live

oaks grow on terraces.

Big Sur is the

southernmost reach of Sequoia Sempervirens –

coastal redwoods – but there are many glorious

examples here of these grand trees. In Pfeiffer Big

Sur State Park, near the group picnic ground, one

of the trees, Colonial Tree, is 27 feet in

circumference. Closer to the Lodge, there is a

grove of 1,200 year old redwoods called the

Proboscis Grove.

|

|

John Steinbeck called California Redwoods,

“Ambassadors from an ancient age.”

|

|

Much of the virgin

redwood in the area was cut when the Ventana Power

Company built a sawmill at the turn of the century.

Although the sawmill was abandoned by the Power

Company in 1906, the Pfeiffer’s continued to use it

intermittently. Florence got the mill back in

running order to cut lumber for guest cabins. The

sawmill ran again during the early 1920s, providing

cut lumber to build housing for people working on

Highway 1.

|

|

|

Big Sur’s remoteness and

rugged terrain helped save some of its natural

resources. Harvesting trees in steep canyons was

difficult, then transporting them to an ocean cove

to be loaded on a ship required complex logistics

and much capital.

Harvesting Big Sur’s

natural resources was made possible in large part

by the elimination of the Native People.

Standing near the southern

limit of their range, coast redwoods are found in

areas along the Big Sur River and smaller creeks in

the park.

Like a royal pageant

through the valley, they lend a serenely grand aura

to the atmosphere. Even when the 200-site

campground is full, there is a quiet amidst the

trees. When a chickadee or a warbler sings, its

melody echoes along the river. A sage and

blackberry aroma wafts through the

Valley.

|

Photo by Phil

Adams

|

McWay Rocks seen from atop Ewoldsen Trail

Photo by Jack

Ellwanger

|

|

Page Twenty-Six

|

|

Back

Country

Wonderful experiences await hikers

east of the coast. Pristine landscapes that look very much

like they did before Europeans arrived. Vast oak savannahs

and magnificent vistas of the Ventana Wilderness and Santa

Lucia Mountains are part of the early California

treasures.

|

|

Hiking in San Antonio Valley

Photo by Margie

Whitnah

|

Mission San Antonio de Padua

Photo by Jack

Ellwanger

|

|

|

The

Rich Marine Environment

Early European hunters

almost entirely eliminated sea otters, gray whales,

red abalone and elephant seals along the whole

Pacific coast. This tradition carried through with

the Americans as the Big Sur region was plucked

almost completely clean of redwoods and

tanoaks.

Elephant

seal pups at San Simeon are part of one of nature’s

most spectacular comebacks. Less than 25 years ago,

this incredible mammal was thought to be extinct. A

few survived and colonized a Mexican island. At the

end of the 1980s they began colonizing in Big Sur,

and today there are more than 8,000 of these

amazing seals on our South Coast.

Photo by Jutta

Jacobs

Elephant Sea Friends of the

Photo

by Margie Whitnah

|

Whales in McWay

Cove are occasionally seen. During the

northern migration, two cows bring a

newborn calf up the coast. The trip is

dangerous as orcas hunt the California

gray whales to kill the calf. The cows

seek the cliffs to help them protect

against orca attacks.

More than 20,000

gray whales make the Arctic to Baja

migration and back each year. It was not

long ago that they were hunted by humans

to near extinction.

|

Songbird

Banding

On Saturday

mornings between Memorial Day and Labor

Day, you are invited to observe how

songbirds are studied.

At the Big Sur

Ornithology Lab (BSOL), the Ventana

Wildlife Society (VWS) records data

about songbirds.

|

Photo

by Margie Whitnah

|

BSOL

biologists, staff, interns, and

volunteers recognize what a unique

place Andrew Molera State Park is for

the hundreds of species of migratory

bird populations who rest and breed

there. These people are profoundly

dedicated to monitoring and researching

the birds’ health and distribution of

not only the migratory birds, but most

importantly, the common birds in the

area. The ongoing mist netting station

where bird banding is performed at the

lab is a primary method in carrying out

the BSOL team’s efforts toward bird,

wildlife, and habitat

conservation.

The Lab hopes

that by sharing in the learning,

visitors will be inspired to increase

their support for wildlife

conservation, respect for Nature’s

wonders, and protection of our

environment’s biological diversity. The

Lab welcomes visitors to their bird

banding demonstrations.

You may visit

on Saturday mornings from Memorial Day

to Labor Day, between 7 a.m. and 12

noon. It is free to the

public.

|

Big Sur is a

wondrous place. So much of nature can be found

here. But much of yourself can be found here,

too.

An incredible effort

has been made by local citizens and state,

county and national agencies to preserve the

natural wonders of Big Sur. It has not been

easy. But the effort is intended for you to

enjoy and learn from it. So indulge your senses,

and stay in touch.

|

|

China

Cove

China

Cove

Photo

by Margie Whitnah

Photo

by Margie Whitnah

Photo

by Margie Whitnah

Photo

by Margie Whitnah

Photo

by Jack Ellwanger

Photo

by Jack Ellwanger

Photo

by Margie Whitnah

Photo

by Margie Whitnah

McWay

Falls and Saddle Rock

McWay

Falls and Saddle Rock

Limekiln

Falls

Limekiln

Falls